Parable? Or Predictive Programming? Pt. 1

How much are films and literature used to condition the public?

NOTE: This essay is part of a new book I’m working on, The Undeclared War: How to Free Your Mind From Deep State Control, and will be combined with a previous essay on the film Children of Men that also examined the concept of predictive programming.

1. Parable & Allegory

Parable? Or predictive programming? What’s the difference? And what about propaganda? How does that fit into the equation? And how will understanding these distinctions protect us? In the ongoing battles of the Undeclared War with the Deep State, it’s good mental hygiene—a flushing of the PsyOp residues. A way to keep your mind free. I do see signs of more souls waking up, especially in polls showing the new low public trust in media has reached. New light from Old Sol, shaking us up with a vigorous solar maximum? (See “Here Comes the Sun”)

A parable, according to my trusty Merriam-Webster dictionary, is “a usually short fictitious story that illustrates a moral attitude or a religious principle.” The Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales, even Grimm’s Fairy Tales in their original, unredacted fierceness are all replete with parables. Simple stories like Hansel and Gretel were quite clearly designed to teach children not to go into the woods alone. They serve an important function in teaching a child about the potential dangers of the world. In that sense, parables are also cautionary tales.

But predictive programming is no fairy tale, at least not in the Disney sense. Perhaps I should have said “allegory” instead of parable. Yet both have something to teach us. Merriam Webster again: “Allegory: the expression by means of symbolic fictional figures and actions of truths or generalizations about human existence.” In its original Greek root word, allegoria, it is to “speak figuratively, or agorein, to speak publicly, from agora—assembly.” From there, we also get “gregarious,” a person considered to be friendly, outgoing. All the better if they’re “hanging out” with Socrates in the agora (marketplace), metaphorically speaking.

Unfortunately allegory and parable are as liable to abuse as any other human construct. As I’ve said before, it’s clear that especially since the end of WWII, Western societies have been under heavy social engineering. The skills learned in military intelligence turned out to be as useful on the home front as in any war. One area that has always been a prime venue for manipulating the public mind is narrative—particularly in the motion picture arts. The Nazis under Goering were the first to fully exploit this tool through radio broadcasts and the films of Leni Riefenstahl, which turned political rallies into pageants of mythic proportions, potent vehicles of political propaganda. [1]

War had always had its propagandists, but prior to the advent of film this had been limited to print journalism and books. Suddenly a new media of mass appeal was there for the taking, and both the Allies and the Germans during the Second World War lost no opportunity to crank out propaganda films. In Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, the film arts were closely controlled by central government agencies, so the range of expression was severely limited. In America, with its well-established Hollywood business model competing on the open market, film directors had more options, even if restricted by wartime budgets.

This wider latitude of creative freedom, coupled with wartime restrictions on energy, gave rise to the film genre known as Film Noir. Inspired by the pulp novels of the 1920s and ’30s, they revealed a much darker, morally ambiguous world. For the first time in American movies, the protagonist or hero was not a shining paragon of virtue—quite the contrary. Typically, he was a “gumshoe” (private detective) ex-con or former policeman fallen from grace due to a fatal flaw and thrown into the dog-eat-dog world of the city streets. Here too there were attempts to use the genre for propaganda purposes, as with The House on 92nd Street (1945), which employed the aesthetics of Film Noir but was really a “true crime” spy story based on an actual espionage case. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover appears in the prologue to set the stage with a law-and-order monologue typical of films of this type. [2] Spoiler: Even the 1955 Mike Hammer mystery Kiss Me Deadly, considered a seminal film in the Film Noir genre, introduces the Cold War subtext of spies attempting to steal nuclear secrets. [3] Film Noir thus preceded the antihero theme of the 1960s Western by some two decades, introducing a level of complexity to characters that the standard hero narrative in Hollywood lacked.

Poets and playwrights since ancient times have used fiction as a means of satirizing or criticizing the follies and excesses of their society. That’s nothing new. What’s new is the mass popularity of the film medium, reaching millions of people around the globe. This makes it a tempting tool for propagandists. Fortunately, the impulse to codify dissent in fiction seems consistent among writers, whether writing for the ancient Greek stage or a Hollywood soundstage. In countries not controlled by a totalitarian government, this allows for a kind of dialogue that alternates between pro- and anti-state, pro- and anti-status quo. Where dissent goes off the rails is when as a class writers are captured by a dominant ideology, as we’ve seen recently in Hollywood. There’s a distinct difference between proselytizing in story and Socratic questioning designed to challenge the status quo.

The new technology of the cheap pulp novel allowed not only authors such as Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Mickey Spillane to create an entirely new genre, they provided the seed bed for many other modern fiction genres such as science fiction, space opera, true crime and of course Film Noir. Even Frank Herbert, creator of the Dune series now considered a foundational pillar of sci-fi, got his start writing for pulp fiction magazines like Startling Stories and Astounding Science Fiction. Philip K. Dick, who also wrote for pulp periodicals, eventually developed his philosophical brand of sci-fi that was the basis for the classic film Blade Runner, albeit in greatly altered form from its source novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? [4]

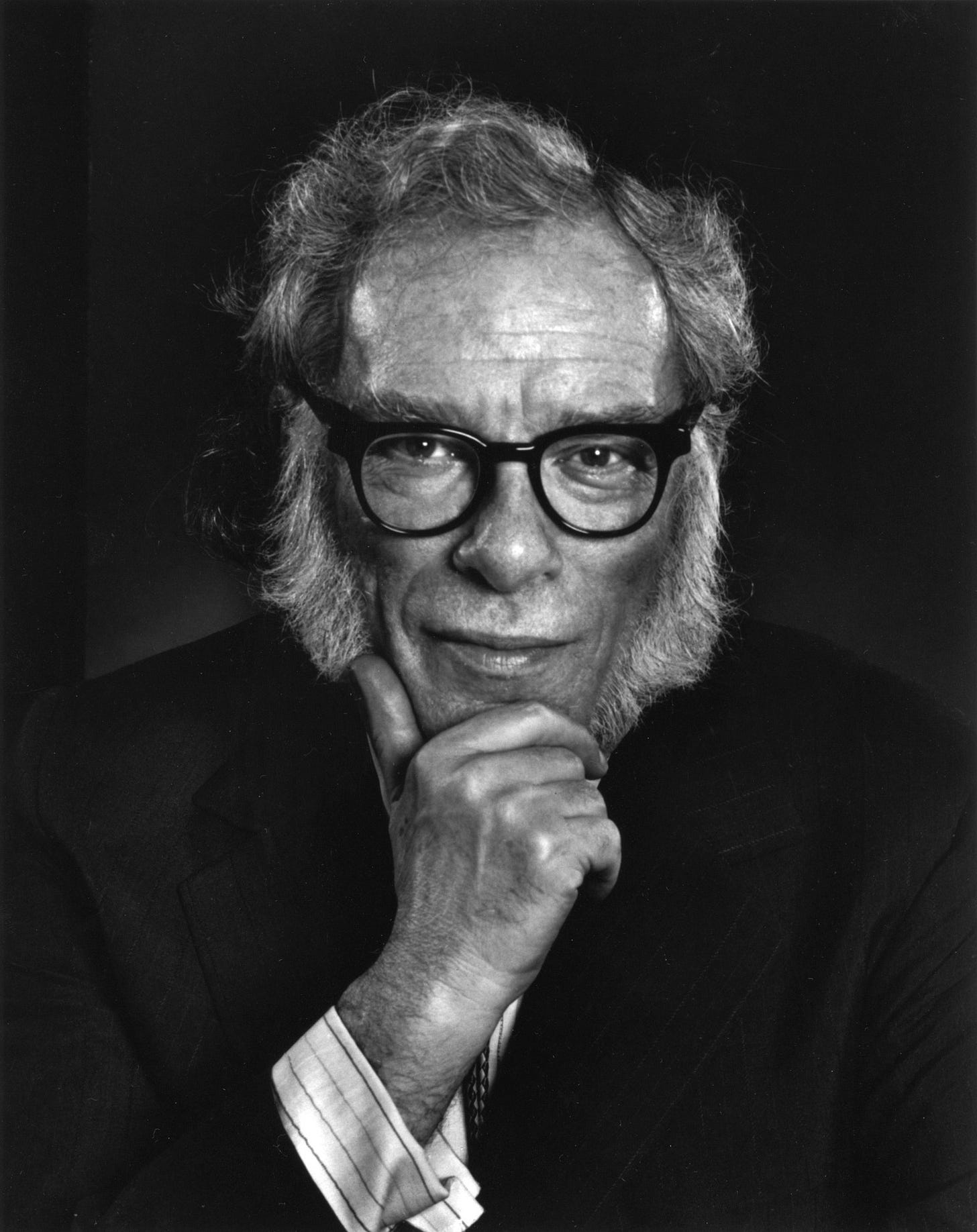

At a time when you could buy a novel for 25 cents, the format launched many a famous writer’s career. Besides the detective and mystery novelists were the early science fiction pulp writers who eventually coalesced into first-class writers of prose, including Isaac Asimov with his Foundation series, the incredibly prolific short story author and novelist Ray Bradbury, whose Martian Chronicles remains a classic of the sci-fi genre, Robert Heinlein, Roger Zelazny, and even the lovably eccentric prose of Kurt Vonnegut, not strictly sci-fi but in his most popular novel Slaughterhouse Five we read a tongue-in-cheek parody of the genre. As a young man I read all these authors with gusto, burning through book after book. Their work was greatly aided by the advent of the space age when the Soviet Union launched its first Sputnik satellite in October 1957. Clearly they were following in the footsteps of Jules Verne, H.G. Wells and Aldous Huxley before them, but taking it much further.

Science fiction to me has always been a vehicle for social satire, not necessarily a predictive or prophetic medium. Today’s Big Tech bros who give grandiose sci-fi names to their software, gaming apps or the recently announced “Stargate” AI initiative—supposedly to create designer mRNA cancer vaccines—seem to have missed this key memo. They see everything in literal terms, as if sci-fi were a form of prophecy that predicts forthcoming technology and social organization. In some respects this is true, as in the case of the flip-phone communicators and touchpads seen in the original Star Trek series. But no matter what the latest theories of quantum physics speculate, it seems highly unlikely we’ll ever see humans transporting across space the way Captain Kirk and crew did. As Dr. Robert Malone explains in his takedown of the “Stargate” AI venture, Larry Ellison, Sam Altman and Masayoshi Son seem either ignorant of medical science or deliberately obfuscating the real purposes of the project. [5]

Today’s transhumanist Bros seem blissfully unaware that the human body’s immune system will reject any foreign material. Even organ transplant patients with a DNA match well above 90% must still take anti-rejection (immunosuppressant) drugs for the rest of their lives. [6] If an organ made of human tissue but originating in another body sparks a powerful immunological reaction, how is a completely artificial item like a brain chip going to avoid this problem? Elon Musk announced the first human volunteer to have a Neuralink chip implanted in January 2024, though there are no updates on the person’s condition since then. [7] Prior to this announcement, Neuralink trials with lab monkeys caused so much suffering in the animals that most of them had to be put down. Although this was initially reported by Neuralink, Musk later denied it. [8] Despite this unpromising start, Musk somehow managed to do an end-run around research safety protocols just two years later with the announcement of the first human volunteer.

Biological limits are nature’s way of saying: You may go this far and no further. It’s what the classical Greek myths of human or semi-divine overreach—the tales of Icarus and Phaeton—were trying to teach us. Other cultures have similar cautionary tales. The Indian epic poem Ramayana contains the story of Jatayu and Sampati, two demigod brothers in the shape of birds. Like Icarus, they fly too close to the sun, and although Sampati shields his younger brother Jatayu from the sun’s heat, his wings are scorched beyond repair and he spends the rest of his life living in the forest as a flightless bird. [9] Flight in ancient stories is often a metaphor for human ambition or imagination, hence the old English expression “flights of fancy.” The key is understanding the difference between “fancy” (fantasy) and reality. Fly too far from the bounds of reality and your wings will be scorched. What kind of arrogance makes today’s technocrats believe that they—of all generations of humanity that have ever lived—will somehow be exempt from this law of nature?

Technologists evidently miss the fact that much of original Star Trek was based on Shakespearian and classical Greek drama—rich sources of allegory and sociopolitical satire. Because special effects technology in the 1960s was still fairly primitive—though 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey stands apart in this respect—a sci-fi series produced for TV on a low budget had to rely on great storytelling to hold an audience. Although nurtured by the ’60s optimism of the American space program, Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry didn’t want his Starfleet to be simply another euphemism for Imperial America. He saw Starfleet primarily as a coalition of explorers, though inevitably this sometimes means conflict. Roddenberry also wanted to break the racial stereotypes of the era, becoming the first to portray an interracial crew, a prime example of a writer cloaking social critique in a space adventure story.

Ursula K. LeGuin, influenced by ’60s feminism, would take it a step further with her portrayal of a matriarchal space colony in The Dispossessed. Rather than merely use the story to lambaste patriarchy, the novel reveals a grasp of human complexity, the shadow side of the feminine psyche when put in a position of ultimate power. Humans are humans, and neither gender is above the abuse of power. They just do it in different ways.

Margaret Atwood—surely one of the most privileged women ever to live—succumbed to feminist harangue with the popular book (and now TV series) The Handmaid’s Tale, depicting an unlikely dystopian future given late 20th century and early 21st century sociological developments favouring women as never before in history. She was far more astute with her Oryx and Crake trilogy, depicting the more likely dystopian scenario of genetically modified organisms run amok on a global scale. Here again, she is exercising the sci-fi author’s prerogative to deeply challenge a contemporary society and its tendency to blunder forward thoughtlessly with new technology. Ironically, though writers are most often found in the libertarian (or libertine) camp, she actually reveals a rare conservative impulse here—to stop and consider carefully before leaping, just as the ancient tales advise.

Samuel Butler beat Atwood to it by about 130 years with his satirical dystopia Erewhon (1872)—a society that has a collective conversation about technology, weighs up the pros and cons, chucks the dodgy, toxic stuff, and keeps the tools that have proven their worth with minimal downside. Of course, he was almost pathetically naïve to hope that any human society would be rational enough to sit down and have such a serious conversation, much less actually agree on anything. But this again is the role of the writer in society—to insist on a higher vision “whose reach exceeds its grasp,” not necessarily because it’s attainable, but because otherwise we too easily give in to our baser nature. Naïveté thus becomes something far more than simple, something the Romantic poets haven’t been given enough credit for. Tennyson with Ulysses’ grand imperative “to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield…”

NEXT: Part 2: Predictive Programming

[1] Leni Riefenstahl, Britannica online: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leni-Riefenstahl

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_House_on_92nd_Street

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiss_Me_Deadly

[4] “Classic Pulp Fiction Writers: The Authors Behind 20th-Century Genre Classics,” Screaming Eye Press: https://www.screamingeyepress.com/pulps/classic-pulp-fiction-writers/

[5] Redacted News, Monday, January 27, 2025, time stamp 1:36:29:

[6] Linda Huante, “Can transplant recipients be “weaned” off anti-rejection drugs?” December 6, 2021: https://www.bswhealth.com/blog/can-transplant-recipients-weaned-off-anti-rejection-drugs The author, a transplant patient, signed up for trials researching the possibility of weaning her off immunosuppressant drugs. Her results were positive, but rare. “The results of this study have not been published yet, but according to James Trotter, MD, Director of Transplant Hepatology at Baylor University Medical Center, it is very rare for liver transplant patients to successfully stop all immunosuppression medications.”

[7] Bill Chappell, “What to know about Elon Musk's Neuralink, which put an implant into a human brain,” January 30, 2024: https://www.npr.org/2024/01/30/1227850900/elon-musk-neuralink-implant-clinical-trial

[8] Hannah Ryan, “Elon Musk’s Neuralink confirms monkeys died in project, denies animal cruelty claims,” CNN Business, February 17, 2022: https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/17/business/elon-musk-neuralink-animal-cruelty-intl-scli/index.html

[9] Jatayu and Sampati, Shmoop: https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/daedalus-icarus/jatayu-sampati.html