Covid-19’s First Great Dystopian Love Story

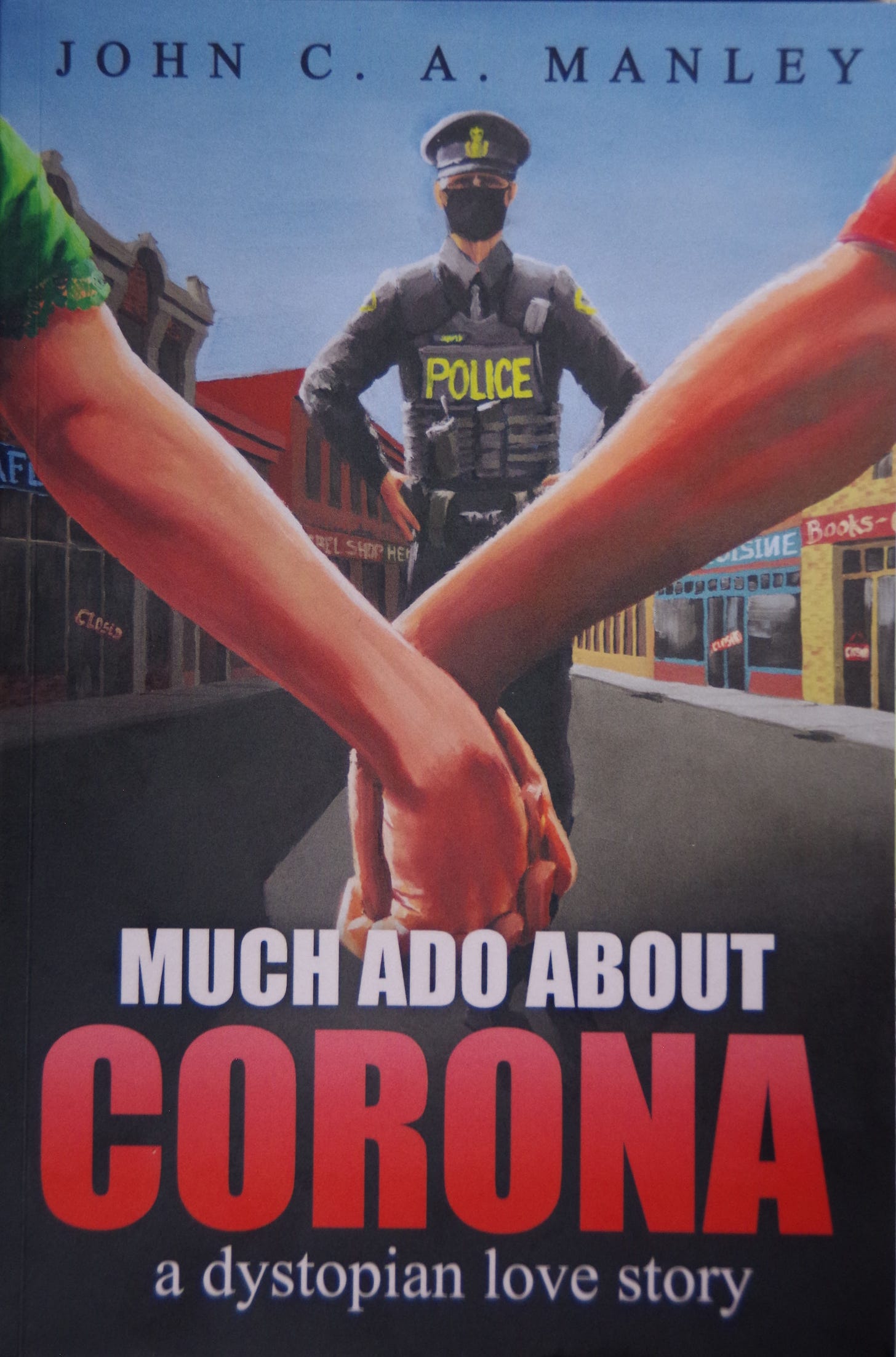

A review of Much Ado About Corona: A Dystopian Love Story by John C.A. Manley

Imagine you lived in an alternate universe for the past two-plus years since the first Covid-19 lockdowns in March 2020. Everything is a mirror image of itself. You walk into a bakery and see a sign that reads: “No Face, No Service,” NOT “Masks are Mandatory.” While this isn’t quite the setup for John C.A. Manley’s first novel, Much Ado About Corona, it’s a clue that in this story it’s the alternate—not the mainstream—perspective that is fully explored. The faint of imagination need not apply.

In fact, that could have been another sign in the bakery window, operated by an attractive young German-Canadian woman named Stephanie Müller. The novel’s protagonist, Vince McKnight, finds himself drawn into her spell even though he firmly believes the line being peddled by government health authorities about masks, social distancing and quarantines. It’s a testament to the enduring power of romantic love to change lives.

Manley cleverly models his “dystopian love story” after the 1823 song cycle Die schöne Müllerin (The Maid in the Mill) composed by Franz Schubert, which Vince hears playing in Müller’s shop. The songs tell the story of a beautiful miller’s daughter who rejects the advances of a young miller who has fallen in love with her, based on a series of poems by Schubert’s friend Wilhelm Müller. [1] According to Wikipedia, “The young man is soon supplanted in her affections by a hunter clad in green, the color of a ribbon he gave the girl. …In the end, the young man despairs and presumably drowns himself in the brook.”

Manley deftly weaves his love story throughout the other main storyline, in which Vince’s gradual conversion to Müller’s perspective on mandates and lockdowns puts him on an escalating curve of confrontation with the police and health authorities. Vince even dubs the beautiful baker “Dandelion,” for her green dress topped with radiant blonde hair, echoing the green ribbon of the original German story.

Like the young journeyman miller in Schubert’s tale, Vince finds himself competing with a fiancé back in Germany, setting up the romantic tension in Manley’s story. To avoid spoilers I’ll leave it at that. Vince quickly finds that even some of his longtime friends, people he’s grown up with, are just as skeptical about the mainstream Covid-19 narrative as the Dandelion. But unlike the outspoken young miller, they tend to fall into what Belgian psychologist Mattias Desmet calls the “soft middle” of the populace—the 60% or so who probably don’t really believe it either but choose to ‘go along to get along.’

However, as the stakes rise in the story, his band of brothers coalesces into a kind of soft power guerilla unit moving from passive to active resistance. Goethe once said: “The moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred… Unforeseen incidents, meetings, and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way.” It’s equally true, as the ancient Greek philosophers understood, that once you cross the threshold of action, you are in the hands of Fate. There will be unforeseen consequences. Courage comes with a price, which is why it seems to have become such a rare quality in today’s world. Yet as John Leake writes in The Courage to Face Covid-19, the ancient Spartan poet Tyrtaeus called courage “mankind’s finest possession,” because it “enables us to do the right thing, to face danger, and to enjoy life. People who live in fear are miserable.” [2] In Much Ado About Corona Manley shows how a single courageous individual can activate the latent courage in others of good conscience.

Manley’s novel is a maple-rich slice of Canadiana, Northern Ontario culture in particular, with its blend of Quebecois, Ojibwe, Métis, Scots-Irish and German cultures. Adding cultural texture to the story, there are snatches of Italian, German, Ojibwe and French languages interpolated throughout the novel. Readers from this part of Canada will immediately recognize themselves, seamlessly woven into the tale. His Quebecois characters are eminently believable; flesh-and-blood individuals that are instantly likeable and memorable. (I still feel sad over the death of one of them.)

Vince is one-quarter Ojibwe, his grandfather full-blood, adding a shamanistic undercurrent to the story that adds a fascinating spiritual dimension, reminding us of Shakespeare’s often-quoted phrase from Hamlet, “there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Manley’s love of Shakespeare is another vivid thread woven throughout the novel; Vince’s grandfather had been incarcerated in residential school as a child but found that the Bard’s plays gave him a lifeline during that miserable experience. Manley lives in Stratford, Ontario, home of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, and his young son Jonah is already showing promise as a Shakespearian actor. The title of the novel itself is of course an homage to Shakespeare’s popular play Much Ado About Nothing, the author’s knowing wink at the audience.

The history of plagues and pandemics reveals certain recurrent patterns when disease strikes. And plenty of medical blundering—no matter what century it is. The fear of death tends to initiate mass hysteria and irrational behaviour. This is ripe territory for exploitation by power-hungry authorities. Manley incorporates into Much Ado About Corona various apt quotations, for example the classic 16th century work by Etienne de la Boétie, Discourse on Voluntary Servitude, which was probably the first to examine why people willingly submit to various forms of slavery and even tyranny:

“It is incredible how as soon as people become governed, they promptly fall into such complete forgetfulness of their freedom. So much so, that they can hardly be roused to the point of regaining it.”

In the centuries since an entire body of literature has been written on this theme, laying the foundations of our knowledge of mass psychology, groupthink and propaganda. For readers interested in exploring this topic further, Gustav Le Bon’s The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) was the pioneer in the field; more recently, Jacques Ellul’s Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes (1965), provides an incredibly fine-grained understanding of the nuances of public manipulation. (And of course Mattias Desmet’s recently released The Psychology of Totalitarianism.) People who think governments would fail to make use of this knowledge are only kidding themselves. As I found in my research for Words from the Dead, leaked documents from Germany, the UK, and Canada, (and likely the US and Australia) made active use of military intelligence units to manage public perception of the pandemic and ramp up the fear. Yet as Vince’s Ojibwe grandfather reminds us through the immortal words of Shakespeare: “So every bondsman in his own hand bears the power to cancel his captivity.” (Julius Caesar)

And captivity indeed describes what most of the world suffered during lockdowns. Multiple studies have now concluded that these lockdowns were ineffective in preventing the spread of coronavirus and ended up creating more harms and deaths.[3] The same was found to be true during history’s previous pandemics. Daniel Defoe, in his account of the 1665 London bubonic plague, A Diary of the Plague Year, was first to come to this conclusion: “…I believed then, and do believe still, that the shutting up of houses thus by force, and restraining, or rather imprisoning, people in their own houses… was of little or no service in the whole. Nay, I am of opinion it was rather hurtful...” [4]

Manley, a first-time novelist (although his bio states he has been writing fiction since childhood), went the extra mile in due diligence, passing his manuscript drafts through a veritable army of beta readers to verify factual details and language translations. Because he has an Ontario Provincial Police officer (spoiler!) undergo a nervous breakdown, Manley made sure to have these portions read by a psychologist as well as by retired police officers. This diligence on the author’s part adds a substantial underpinning of reality to the novel, and except for the fictional characters, at times it reads like a well-researched non-fiction narrative.

From a literary perspective, Much Ado About Corona could be said to be an “activist novel,” much like my own novel Mountain Blues. At times one gets the impression of reading a kind of truth serum data download. However, given the skill with which it was written, this does not demean it. As George Orwell said in his famous essay, “Why I Write,” “In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer… Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism... It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects... The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.” [5] Manley, like his fictional characters, has demonstrated courage by facing up to the crushing issues raised by the pandemic. This is more than most of Canada’s writers have done. As I wrote on Substack, [6] the blatant censorship and abuses of the Canadian Charter during lockdowns were met with a deafening silence by both the Writers’ Union of Canada and the writers’ community in general.

As someone who should know, Vince’s Ojibwe grandfather sums up the experience of the pandemic with great wisdom: “Never doubt what evils are possible in this world. And what good it will bring out in those who try to stop it.” In that respect, the characters so vividly brought to life in Much Ado About Corona have a connection with the great heroes of literary history stretching all the way back to Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey. These are not comic book heroes with supernatural powers but ordinary, flawed but gifted individuals who find themselves compelled by both the gravity of the times and their consciences to fight for freedom.

To order the book or subscribe to news feeds from John Manley visit: MuchAdoAboutCorona.ca An author biography is here: https://blazingpinecone.com/about/ The author is writing a sequel to the story.

Full disclosure: I was hired by Manley to do a line edit of an early draft of the manuscript. In a true case of serendipity or synchronicity, around the same time as he was writing and decided on the dandelion metaphor, I published a poem in Diary of a Pandemic Year which uses the metaphor of the dandelion to illustrate the human spirit’s capacity for resistance: “…the human spirit / a dandelion crushed beneath robotic boots. / Don’t underestimate that green insurgent. / We’ve seen it split open pavements, deploy / its yellow parasols on long milky necks…”) [7] Or as Manley writes in the Prologue, “proving how the seemingly inconsequential can alter the direction of the large and powerful.”

[1] Maureen Buja, “A Life in a Circle: Schubert’s Die Schöne Müllerin,” https://interlude.hk/a-life-in-a-circle-schuberts-die-schone-mullerin/

[2] John Leake and Dr. Peter McCullough, The Courage to Face Covid-19, Counterplay Books, Dallas, Texas, 2022, p. 10.

[3] Douglas W. Allen (2021): Covid-19 Lockdown Cost/Benefits: A Critical Assessment of the Literature, International Journal of the Economics of Business: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13571516.2021.1976051 Dr. Paul Elias Alexander, “More Than 400 Studies on the Failure of Compulsory Covid Interventions (Lockdowns, Restrictions, Closures),” November 30, 2021: https://brownstone.org/articles/more-than-400-studies-on-the-failure-of-compulsory-covid-interventions/ Dr. Denis Rancourt, “Measures do not prevent deaths, transmission is not by contact, masks provide no benefit, vaccines are inherently dangerous: Review update of recent science relevant to COVID-19 policy,” special report to the Ontario Civil Liberties Association, December 28, 2020: https://denisrancourt.ca/entries.php?id=12&name=2020_12_28_measures_do_not_prevent_deaths_transmission_is_not_by_contact_masks_provide_no_benefit_vaccines_are_inherently_dangerous_review_update_of_recent_science_relevant_to_covid_19_policy

[4] Daniel Defoe, Journal of the Plague Year, Sea Wolf Press edition, 2020, p. 61.

[5] George Orwell, “Why I Write” (1946), The Orwell Foundation: https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/why-i-write/

[6] Sean Arthur Joyce, “Writers Abandon Their Role as Social Critics,” Substack, June 9, 2022:

[7] Sean Arthur Joyce, “Cashless,” from Diary of a Pandemic Year, Chameleonfire Editions, 2021: https://www.seanarthurjoyce.ca/diary-of-a-pandemic-year